We learn about the world through our senses:

![]() hearing sounds – hearing your phone beep tells you you’ve got a text

hearing sounds – hearing your phone beep tells you you’ve got a text

![]() seeing sights – a car driving towards you tells you it’s not safe to cross the road

seeing sights – a car driving towards you tells you it’s not safe to cross the road

![]() smelling smells – the smell of burning tells you to turn off the grill!

smelling smells – the smell of burning tells you to turn off the grill!

![]() tasting flavours – to find out if something is sweet or sour

tasting flavours – to find out if something is sweet or sour

![]() touching different things – to find out if clothes are wet or dry, or if the radiator is hot or cold

touching different things – to find out if clothes are wet or dry, or if the radiator is hot or cold

![]() feeling movement – if you close your eyes on a train you know if you’re going forwards or backwards.

feeling movement – if you close your eyes on a train you know if you’re going forwards or backwards.

Your baby uses the same senses to find out about the world. Some of the young baby’s senses are different to an adult’s when they are born. As they grow, their senses help the baby to make ‘sense’ of the world!

Hearing

Babies are able to hear in the womb, and they learn the sound of their mother’s voice before they’re even born. Babies in the womb from even 12 weeks gestation show reactions to different sounds.

Babies are able to hear in the womb, and they learn the sound of their mother’s voice before they’re even born. Babies in the womb from even 12 weeks gestation show reactions to different sounds.

From about 6 months gestation they can hear pretty clearly. Researchers have shown that if a mother repeatedly reads the same story out loud before the baby is born, the baby will recognise it if someone reads it when they are born.

Newborns can tell where a sound is coming from (left or right, far or near), but it takes a few months for them to pinpoint the exact place.

Newborns can tell where a sound is coming from (left or right, far or near), but it takes a few months for them to pinpoint the exact place.

Before 6 months of age, babies are actually better at hearing word sounds than adults are! Babies are born with the ability to hear the sounds of all the languages in the world.

Different languages have different sets of sounds, so you don’t need all of the sounds for each language. After about a year, babies adjust to the culture they live in and tune in to their native language sounds, losing the ability to hear sounds from other languages. This is why French speakers have difficulty with the “th” sound in English — French doesn’t use a “th” sound.

Ever wondered why people talk to babies in high-pitched baby voices? Researchers think these high sounds are actually easier for the baby to hear, and that it helps them to learn about language.

Seeing

When they are born babies can only see 1/30th of the fine detail that a grown up can, so everything is pretty blurry! They’re also not very good at focussing their eyes on things. They have been found to see things best when they are around 25 cm (10 inches) away from their eyes. Here’s a picture of what a grown up can see, and below, what a baby would see of the same scene.

Over the first weeks, months and years of life, vision improves slowly. Different abilities grow at different rates as the baby’s eyes and brain mature. Researchers think that newborn babies probably see mostly in black and white, with colour vision improving over the first year.

From birth, babies can tell different shapes apart. They have to learn to use their two eyes together in the first few months of life. They can make out features like stripes around 6 weeks of age, and can notice things moving around 10-12 weeks of age.

The ability to see depth (like the drop between the bed and floor) is firmly in place by 6 months of age, and they learn important ideas about shapes during these 6 months as well. (See the Check it out! box below).

Babies are also able to perceive faces from birth, and within a few days they can tell the difference between their mother’s face and strangers’ faces. They also show preference for faces that adults consider attractive.

Newborn babies often copy the facial expressions of adults, like smiling or sticking out their tongues. This shows that they can see the detail of the faces. By about 6 months, a baby can recognise a parent across a room.

Babies are also better than adults at telling the differences between non-human faces, like monkey faces. But they lose this ability by 10 months of age as they don’t see monkey faces enough to need this ability any more. This shows that nature gives us lots of skills, but we only keep the ones that we need in the world we are born in to.

Check it out!

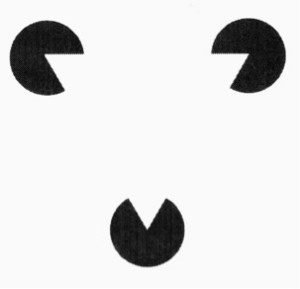

From looking at this picture, you can probably see how the outline suggests the shape of a triangle in the centre, even though there is no triangle there. Researchers have found that babies as young as 3 months also pick out the missing shape.

They tested this by showing the baby an image like this, then showing them the missing shape, or a different one. Babies showed more interest in the different shape, which suggests they were bored of seeing the triangle by then! Find out more about experiments like this in How do we study babies?

Touch

Babies react to touch well before they’re born. From around 8 weeks gestation, researchers have found that the unborn baby responds to touch when they insert a soft wire in to the uterus (sounds horrible but it’s safe, don’t worry!).

At first, the unborn baby will move away from the touch or curl up the body part that’s being touched (e.g., the hand), but as they develop, they will start to move towards the touch.

As a young baby, touch is a really important part of learning about the world. You have probably noticed that babies put everything in their mouth—toys, the TV remote, their feet! This ‘mouthing’ is actually because they have very sensitive mouths, so they can find out a lot of information about texture and taste by using their mouths (but you’ve got to be careful they don’t mouth anything dirty or anything that they can choke on!).

As a young baby, touch is a really important part of learning about the world. You have probably noticed that babies put everything in their mouth—toys, the TV remote, their feet! This ‘mouthing’ is actually because they have very sensitive mouths, so they can find out a lot of information about texture and taste by using their mouths (but you’ve got to be careful they don’t mouth anything dirty or anything that they can choke on!).

Babies also have very sensitive skin, and exploring the feeling of different textures on their skin can teach them a lot. They love tickling and by the time they’re a few months old, babies will laugh and find tickling games very funny. And of course, cuddles and the warmth of being held close are important for a baby to feel safe and loved.

Smell and Taste

Smell seems to be the most developed sense a baby has at birth. Even in the womb it seems that babies might detect mother’s perfume or tastes from her diet.

Also, when pregnant women eat it can make the amniotic fluid in the womb taste sweet, and this makes the foetus in the womb swallow fluid more regularly – so even before they are born babies have a sweet tooth!

Newborns can recognise the smell of breast milk, and tell the difference between the smell of their mum’s breast milk and another woman’s. They will also recognise smells of some foods that their mother ate when she was pregnant, like garlic, anise and carrot juice.

Some parents use this information on smell to help soothe their baby when they’re upset. So cuddling up with a nightdress that smells like the baby’s mother can sometimes help to comfort a baby who is crying.

Movement

Unborn babies are sensitive to movement. We know this because they tend to be quiet during the day when their mothers are busy moving about, giving them lots of stimulation. At night, when mums want to rest and sleep, they get more active and start to jump and twirl about!

The stimulation the baby gets from movement seems to be good for them. Babies born prematurely do better later on if their incubator is gently rocked instead of sitting still, or if they sleep on waterbeds instead of mattresses.

When babies are born, the doctor will check their movement reflexes, which show ways that the baby’s body responds to sudden movements, like falling. Every baby is born with these reflexes, and they gradually go away as the baby grows.

When babies are born, the doctor will check their movement reflexes, which show ways that the baby’s body responds to sudden movements, like falling. Every baby is born with these reflexes, and they gradually go away as the baby grows.

In the first year, babies spend about 5% of their waking time doing the same movement over and over again—kicking legs, waving arms, swaying, banging objects or bouncing up and down. These movements are believed to be important for the brain and muscles to learn new physical movements.

Babies are also comforted by the feeling of being gently rocked, and this is a time-honoured way of helping a baby fall asleep.

Understanding the World

It can be hard for researchers to figure out what a baby can think about or understand about the world around them. When researchers talk about ‘thinking’, they generally mean things like what a baby can picture in his or her mind, what they can remember, pay attention to or how they can solve problems.

When you think about a car, you can probably picture one in your mind, right? And if someone asked you how you open a door, you could explain how you do an action (push down the handle, pull or push the door), and the other action follows (the door opens). You learned these things about the world by living in it, and solving different problems, and you store this understanding in your mind so you can think about it whenever you want to. So how do babies learn all of this stuff,and when?

Researchers have tried to answer these questions by studying baby’s reactions to different actions and objects, at different ages. Their general idea is that babies’ thinking goes through different stages that allow them to see the world in more and more complex ways.

Researchers have tried to answer these questions by studying baby’s reactions to different actions and objects, at different ages. Their general idea is that babies’ thinking goes through different stages that allow them to see the world in more and more complex ways.

During these stages, the kinds of input or stimulation they receive are really important to help to move through those stages. So the baby’s brain and their environment are both really important ingredients in helping a baby to learn.

There’s no way a baby’s brain could understand something complex like long multiplication when they are a few months old, as their brain just isn’t ready for it yet.

But when they’re older and their brain is ready, they will need somebody to show them or teach them how to do it. So understanding a baby’s mental development means taking in to account their brain and their environment.

Understanding Numbers

Researchers have wondered how much babies understand about numbers. They have found that babies around 3 and 4 months old show surprise if it looks like there are more objects hidden behind a screen than could actually fit there. So very small babies seem to have some understanding of quantity, or numbers of objects.

Researchers have wondered how much babies understand about numbers. They have found that babies around 3 and 4 months old show surprise if it looks like there are more objects hidden behind a screen than could actually fit there. So very small babies seem to have some understanding of quantity, or numbers of objects.

Babies between 4 and 7 months old have also been tested to see if they understand numbers. They were given a number of dots to look at (2 or 3), and then either a different number of dots or the same one again. Babies showed more interest in the new number, which shows that they might be noticing the difference between the two sets of dots.

Babies as young as 6 months also show surprise if the answer to an addition game is wrong. One doll is placed on a stage, then hidden behind a screen. Another doll is added, which the baby can see happening, but then the experimenter plays a trick and hides one of the dolls before taking down the screen. The baby shows surprise by looking more at the wrong answer than babies who see the right answer, as though they were expecting there to be two dolls.

Understanding Objects…or not!

One really important part of learning about the world is for babies to understand what different objects are, what they can do and how they work. Researchers think that babies are born with some rules about what objects can do, and develop some more rules from what they see and do in the world.

These rules get more complicated the more they interact with the world, and especially from being surprised by actions happening around them.

Young babies don’t seem to realise that objects still exist when they can’t see them. Researchers found this out by showing young babies toys that they liked, and then covering them up with a blanket. The babies didn’t try to look for them, and seemed to forget all about them. It’s useful to know this, especially if your baby really wants something they can’t have!

Young babies don’t seem to realise that objects still exist when they can’t see them. Researchers found this out by showing young babies toys that they liked, and then covering them up with a blanket. The babies didn’t try to look for them, and seemed to forget all about them. It’s useful to know this, especially if your baby really wants something they can’t have!

By 8 months of age, when the toy was partly covered up, so that a bit was sticking out, the babies could find it. But they still couldn’t find a toy if it was fully covered. Babies will be able to do this by the time they’re 12 months.

So it takes this long for babies to understand that things continue to exist when we can’t see them. This is why, in the last few months of their first year, babies start to get upset when you leave them. They now realise that you do still exist when you can’t be seen and have just gone somewhere else – and they want you back!

But even when they can find a hidden toy, babies still don’t fully understand the object world. Watch this amazing clip, called A not B, of a baby being fooled when you move the hiding place.

Some researchers think that babies understand the object world much earlier—the trouble is, they can’t link their understanding of objects to their actions and so they make errors. There are lots of disagreements like this in developmental psychology, and this is what keeps researchers asking questions and running experiments!

You can find out more about this in the section How do we study babies.

Make-believe

A very important ability comes about in the second year of life, when babies are one year old. This is the baby’s ability to pretend. It is linked really closely to their social development too.

A very important ability comes about in the second year of life, when babies are one year old. This is the baby’s ability to pretend. It is linked really closely to their social development too.

They can start to pretend that a doll is really a baby, or that a banana is a telephone! This might become a big part of their play, such as pretending that dolly is going to sleep or getting her bottle, or that they are a builder filling up the truck and emptying it again.

This is a really important discovery for the baby. It shows their growing understanding that we can look at the same object from different perspectives (for example a banana can be something to eat, or a telephone, or a see-saw, depending on what we decide it is).

Hi ho, hi ho, it’s off to work we go

When your baby plays with you, or plays with toys, they are actually very hard at work! Babies learn so much through play.

When your baby plays with you, or plays with toys, they are actually very hard at work! Babies learn so much through play.

When babies play with you, it actually helps their mind and brain to grow, and teaches them about language, social interaction, feelings. It also gives you a chance to tune in to your child, to figure out what they’re thinking, to understand what they like and don’t like, and to have a giggle with them.

Have a look at different ideas for play in the section Ideas for Play.